Straight Labyrinth Seal Leakage Calculation¶

In its simplest form a labyrinth seal consists of a series of fins and corresponding chambers, forming a restriction to the flow and volume for expansion respectively. Labyrinth seals work by throttling the flow through successive openings in series. In each throttle, static pressure difference accelerares the flow and some of the kinetic eneergy associated with the flow is dissipated by turbulence induced by the intense shear stress and eddy motion in the next chamber.

Labyrinth seals use was first implemented in steam turbine by Parsons in 1892. They have further been successfully used in a wide variety of turbomachinery such as gas turbine and as components in centrifugal compressor dry gas seals.

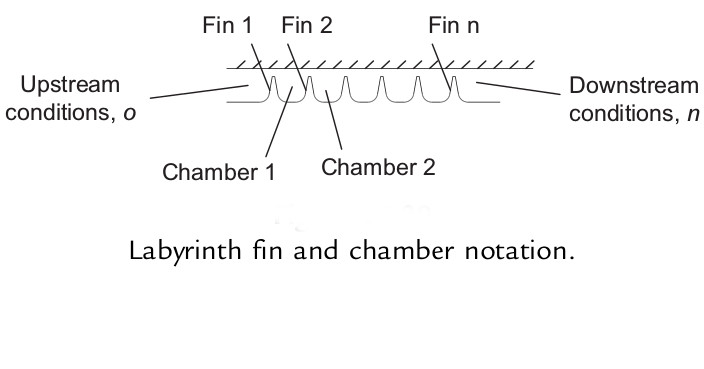

The following figure gives a descriptive notation of the labyrinth fins and chambers and upstream downstream pressures across which the leakage flow occurs.

Labyrinth seals may have a variety of geometries. Some common forms of labyrinth seal include:

- straight through

- stepped

- staggered

Straight through labyrinth seals are simple and are most common. This calculation presently supports leakage rates in straight through labyrinth.

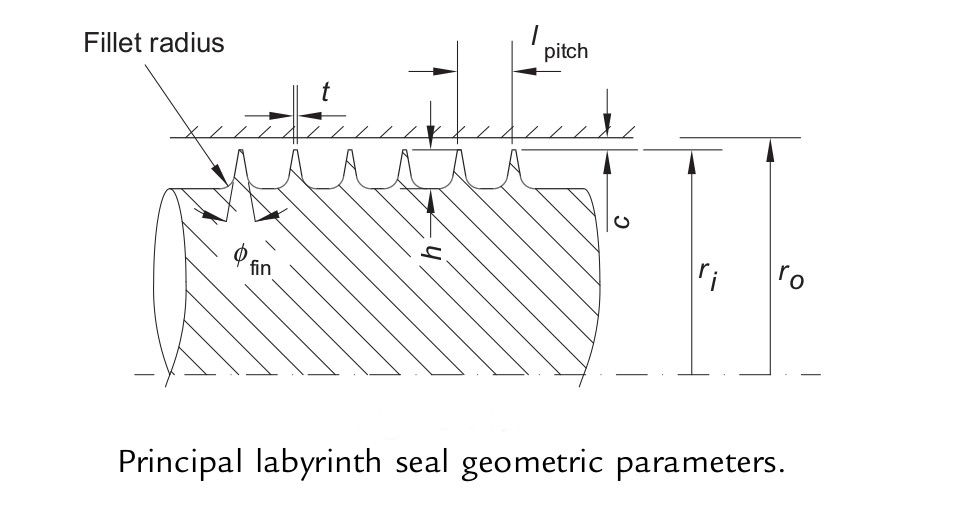

The following figure the principal geometric parameters that affect the performance of the labyrith seal. These parameters are used as inputs in the leakage calculations.

Under design operation labyrinth seals are essentially a controlled clearance seal without rubbing contact. As there is no surface to surface contact, very high relative speeds are possible and the geometry can be arranged to limit the leakage to tolerable levels. Leakage is however, inevitable and can be quantified using empirical methods or using CFD. Labyrinth seals have been the subject of extensive study and a number of empirical and analytical models have been developed.

An analytical approach based on a simplified gas dynamics approach that models the the leakage in the seal as a flow of ideal gas through a series of orifices was originally developed by Martin. Martin assumed that all of the kinetic energy in each cavity or throttling chamber was completely dissipated before the flow passed on to the next cavity. Martin also assumed that the flow was isothermal to further simplify the calculations.

The martins equation is expressed below:

where

\(A\) is the annular clearance area of the annular seal

\(p_{t0}\) is the upstream total pressure

\(p_n\) is the downstream static pressure

\(R_g\) is the specific gas constant

\(T_{t0}\) is the upstream total temperature

\(n\) is the number of fins

The mass flow function \(Q\) provides a convenient means for comparing the relative performance of different seals. This is defined by

Substitution for the mass flow function in equation above gives:

In real practical application the labyrinth seal flow deviates from the ideal assumptions made by Martin in arriving at the analytical solution. For example, only a fraction of dynamic head is lost in the fin and effects of contractions and coatings also need to accounted. Martins equation tends to overestimate the mass leakage rate. Zimmerman and Wolf (1998) proposed some corrections to the Martins original equations based on experimental measurements.

Zimmerman and Wolf introduced a carryover factor and a discharge coefficient factor to make the prediction more accurate. The carryover factor