CHAPTER 2. - FIRST LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS¶

While analysing any thermodynamic system, the universal principles of conservation of mass and energy must stand demonstrated in the mathematical model. The method to mathematically invoke these principles in analysis is presented in the sections below under mass balance principle and energy balance principle.

Mass Balance Principle¶

The principle of mass balance (which follows from the law of conservation of energy) can be stated as:

where,

\(m_{in}\) is mass going in to the system

\(m_{out}\) is mass going out of the system

\(\varDelta m_{system}\) is the change in mass of the system.

In time rate form this can be written as:

Under steady state conditions \(\dot{m}_{system}=0\), hence

For a single stream moving in and a single stream moving out, we have:

where subscript \(1\) denotes the inlet stream and subscript \(2\) denotes outlet stream.

Making use of the relationship \(\dot{m}=\rho\dot{\mathbb{V}}=\rho VA\) , where \(\dot{\mathbb{V}}\) is the volumetric flow rate, \(\rho\) is density, \(V\) is fluid velocity and \(A\) is the fluid flow area we can write the mass balance equation (4) as:

For incompressible flows, the density at inlet (\(\rho_1\)) and outlet (\(\rho_2\)) are the same and so the mass balance equation can be simplified to:

Energy Balance Principle¶

The principle of energy balance (which follows from the law of conservation of energy) can be stated as:

where,

\(E_{in}\) is energy going in to the system

\(E_{out}\) is energy going out of the system

\(\varDelta E_{system}\) is the change in energy of the system.

In time rate form this can be written as:

Under steady state conditions \(\dot{E}_{system}=0\), hence

First Law Analysis for Closed Systems¶

Energy Balance for Closed Systems¶

In the case of closed system no mass enters or leaves the system. However, mass balance principle which applies can still be evoked for the sake of mathematical rigour.

The energy balance principle as given in equation (7) can be invoked in thermodynamic context of a closed system with \(E_{in}\), \(E_{out}\) and \(\varDelta E_{system}\) as given below:

where,

\(Q_{in}\) is heat going in to the system

\(Q_{out}\) is heat going out of the system

\(W_{in}\) is work done on the system

\(W_{out}\) is work done by the system

\(\varDelta U\) is the change in internal energy of system

\(\varDelta PE\) is the change in potential energy of system

\(\varDelta KE\) is the change in kinetic energy of system

Upon substitution in energy balance equation (7), we have,

To further simplify the above, let us use the expressions of net heat (\(Q\)) moving in to the system and net work (\(W\)) done by the system i.e. :

Substituting in (11) we get the first law equation of thermodynamics for closed system i.e.

For the typical case of a stationary closed system, the potential and kinetic energy terms can be set to zero. So, First Law in stationary form can be written as:

First Law in differential form can be written as:

First Law in time rate form can be written as:

Dividing by mass \(m\) we get First Law in specific quantity form as:

Concept of Boundary Work¶

In the context of closed system, we need to expand our idea of work, to include a special form of work that happens when a closed system undergoes expansion or compression. This special form of work which happens because of the motion of the boundary enclosing the closed system is termed as boundary work. In classical mechanics the work done is described by the mechanical work equation as given below:

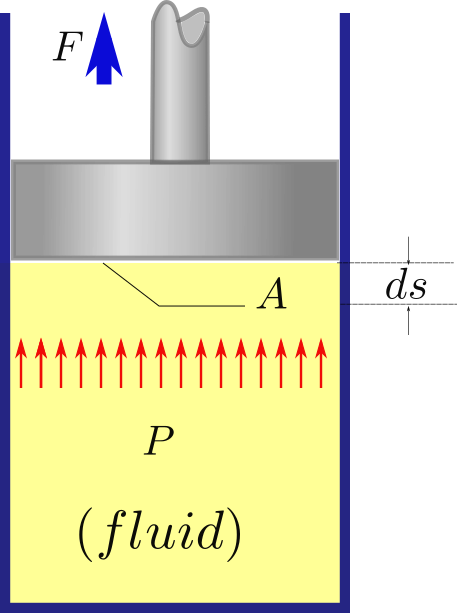

To exemplify a closed system let us take the example of a cylinder piston arrangement as shown in figure.

The cylinder has an internal pressure (\(p\)) and the force (\(F\)) acting on the piston face of a given area (\(A\)) will be \(F=pA\). Substituting this in the mechanical work equation (17) we get the following:

Since \(dV=Adx\), on substitution in the above we get the boundary work equation:

First Law Equation (Boundary Work Form)¶

There may be several types of work interactions acting on a closed system. Boundary work is just one of the various work interactions for the system. So in general terms,

Having developed the expression of boundary work as applicable to closed system (18), the first law equation (12) upon substitution of \(W\) gives the following equation:

Most closed systems are stationary in nature and hence the change in potential and kinetic energy is zero (\(\varDelta PE=0\) and \(\varDelta KE=0\)). In a large majority of cases, the only applicable work is the boundary work and hence, \(W_{other}=0\). Thus we can simplify the above equation to:

Important

First Law equation for closed system (Boundary Work form)

While analysing any closed system process, certain idealizations are required to be made to simplify the mathematics. A process may have to be treated as isochoric, isobaric, isothermal, adiabatic or polytropic. A brief on what these are given in the following sections. In each of these processes, the boundary work term must be evaluated and plugged in equation (19) or (20) . An evaluation of boundary work for each of these processes is now discussed. This is no more complicated than working out a correct mathematical integral of \(\int PdV\), using an appropriate relationship between \(P\) and \(V\)

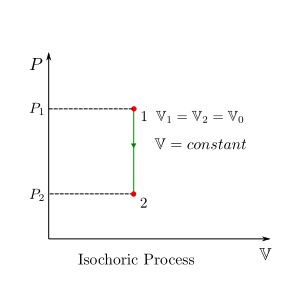

Isochoric (Constant-Volume) Process¶

For a constant volume process, the volume of the system remains fixed and hence \(dV=0\) and consequently the boundary work

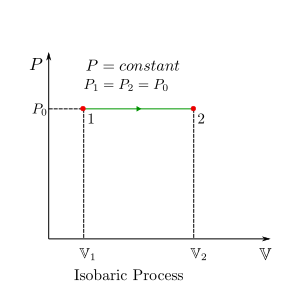

Isobaric (Constant-Pressure) Process¶

For a constant pressure process, \(P=P_0\) where \(P_0\) is the constant pressure. Hence, boundary work is given by:

therefore

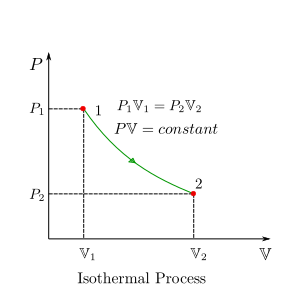

Isothermal (Constant-Temperature) Process (Ideal Gas)¶

For a constant temperature process, \(T=T_0\) where \(T_0\) is the constant temperature. For an ideal gas the following relation holds:

or,

where,

\(m\) is the mass of the gas in the closed system

\(R_{g}\) is the specific gas constant (\(\frac{R}{MW}\))

\(C\) is a constant used for simplicity

Hence boundary work for isothermal expansion/compression can be written as:

or substituting the value of \(C\) from (23),

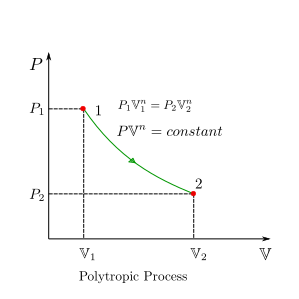

Polytropic Process¶

A study of actual expansion and compression processes in most practical situations reveal that the pressure \(P\) and volume \(V\) are related by the following equation:

where \(n\) and \(C\) are constants. Under these situations we can express \(P\) as :

boundary work can then be written as:

we can make use of the fact that \(C=P_1\mathbb{V}_1^n=P_2\mathbb{V}_2^n\) in the above equation and get the equation for boundary work in polytropic process as:

For an ideal gas gas \(P\mathbb{V}=mR_gT\), and therefore we may also write:

Polytropic process is a very generalised process model. Specific values of polytropic exponent \(n\) lead to specific processes for example,

For \(n=0\) is an isobaric process

For \(n=+\infty\) is an isochoric process

For \(n=1\) is an isothermal process

For \(n=\kappa\) is an adiabatic process

Isentropic Process¶

Isentropic Process is a special case of Polytropic process where \(n=\kappa\). By substituting the same in (26) and (26) we get :

where,

First Law Analysis of Controlled Volume System¶

Mass & Energy Balance for Controlled Volumes¶

In the case of controlled volume system mass may enter and leave the system. For a system in steady state, the rate of mass flowing in equals that flowing out. Invoking mass balance principle in steady state system (3) we get:

for a single stream we can write this as:

The energy balance principle for steady state as given in (9) can be invoked in the context of a controlled volume system with \(\dot{E}_{in}\) and \(\dot{E}_{out}\) as given below: state.

where,

\(\dot{Q}_{in}\) is the rate at which heat goes into the system

\(\dot{Q}_{out}\) is the rate at which heat goes out of the system

\(\dot{W}_{in}\) is the rate at which work is done on the system (power in)

\(\dot{W}_{out}\) is the rate at which work is done by the system (power out)

\(\lambda_{in}\) is the rate at which energy is transported by an incoming stream.

\(\lambda_{out}\) is the rate at which energy is transported by an outgoing stream.

Upon substitution in energy balance equation (9), we have,

To further simplify the above, let us use the expressions of net heat transfer rate(\(\dot{Q}\)) moving in to the system and net work rate (\(\dot{W}\)) done by the system i.e. :

Substituting in (30) we get :

The rate of energy transfer by incoming and outgoing mass ( \(\lambda\)) needs to be elaborated further to evolve this equation in to a more useable form. To understand this energy term, the concept of flow work, needs to defined which applies to flow processes or controlled volumes.

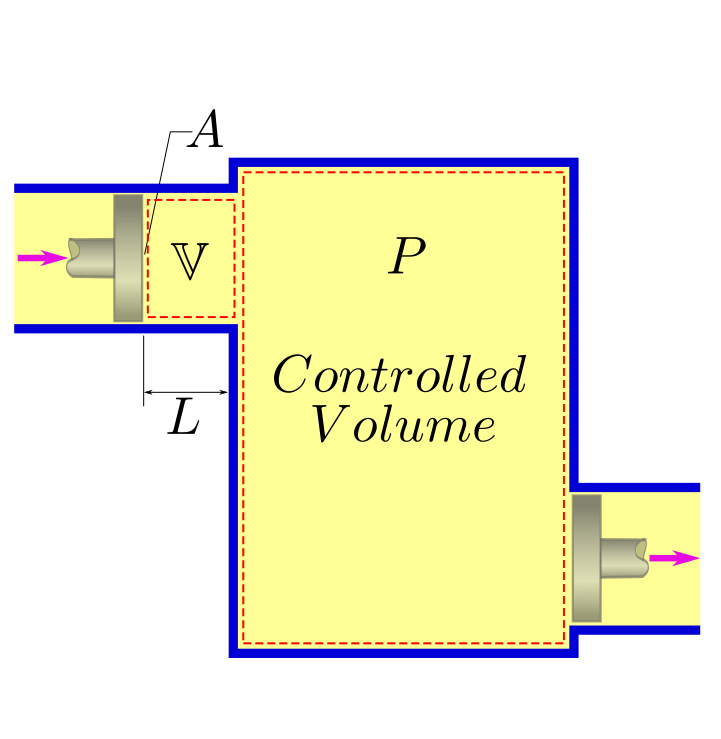

Concept of Flow Work¶

Just as in the case of closed systems, we need to enhance our idea of work for controlled volume systems as well. A special form of work applies in this case which is termed as flow work.

In a flow process, Work is spent to push the fluid into the system. To help our imagination, let us assume that there is a tiny packet of length \(L\) which is about to enter the system through an area \(A\). The system has a pressure of \(P\). This packet is being pushed by the fluid behind, which can be imagined to act like a piston, The work that this piston has to do to push this packet completely in is:

The flow work performed per unit mass can be written as:

A similar work is retrieved (sign shall be negative) as fluid moves out of the control volume, pushing the gas downstream.

Though this is work, while working with flow process in controlled volumes it becomes convenient to treat it like an energy associated with the stream. So this is also sometimes referred to as flow energy.

First Law Equation (Enthalpy Form)¶

The energy transported by stream of fluid moving in to a controlled volume constitutes of the internal energy, potential energy, kinetic energy as well as the flow energy. Thus, on per unit mass terms this can be expressed as:

The individual terms on the right hand side can be substituted as follows:

specific Work Flow energy \(w_{flow} = Pv\) from (33)

specific Potential energy \(pe = gz\), where \(z\) is the elevation from datum

specific Kinetic energy \(ke = \frac{1}{2}V^2\), where \(V\) is the fluid velocity

After substitution in (34) we get:

The quantity \(Pv + u\) occurs invariably in all flow problems and hence a new property enthalpy is defined just to help simplify matters. Thus enthalpy is defined as:

where,

\(u\) is the internal energy per unit mass

\(P\) is pressure of the flow stream

\(v\) is specific volume

Substituting \(h\) in the equation (35) above we get,

The rate at which energy is transported by a mass stream can now be expressed as:

Using this expression of stream energy rate (\(\lambda\)) we can write (31) as follows:

Important

First Law equation for controlled volumes (steady state and multiple streams)

For the most popular case of single stream in and out of controlled volume and acknowledging that under steady state \(\dot{m}_1 = \dot{m}_2 = \dot{m}\) we get the first law equation as applicable to controlled volumes:

Important

First Law equation for controlled volumes (steady state and single stream)

Dividing both sides of the equation by mass flow rate (\(\dot{m}\)), we get the equation on per unit mass basis:

Important

First Law equation for controlled volumes (steady state and single stream) on per unit mass basis

if the changes in kinetic and potential energies can be neglected, then the above further simplifies to:

Important

First Law equation for controlled volumes (steady state and single stream) on per unit mass basis with neglible potential and kinetic energy changes

In the subsequent part of this chapter we shall look into the application of these equation to various devices like nozzles, diffusers, compressors, expanders, throttle valves and mixers etc.

Nozzles and Diffusers¶

Nozzles and Diffusers are used in propulsion jet engines, rockets and stationary aerodynamic components of compressors and turbines etc.

A nozzle is a device that increases the velocity of the fluid at the expense of pressure.

A diffuser is a device that increases the pressure of the fluid at the expense of velocity.

In both these devices the heat transfer can be neglected (\(q=0\))as the time period of interaction is very short. Since there is no work done on or by the device we also have (\(w=0\)). The change in elevation is also negligible and therefore we can consider (\(z_2 = z_1\)).

Thus the first law equation for controlled volume (38), after using the above substitutions becomes:

Tip

For nozzles, \(V_2 > V_1\) and hence \(h_2 < h_1\), so a cooling effect is observed.

For diffusers, \(V_2 < V_1\) and hence \(h_2 > h_1\), so a heating effect is observed.

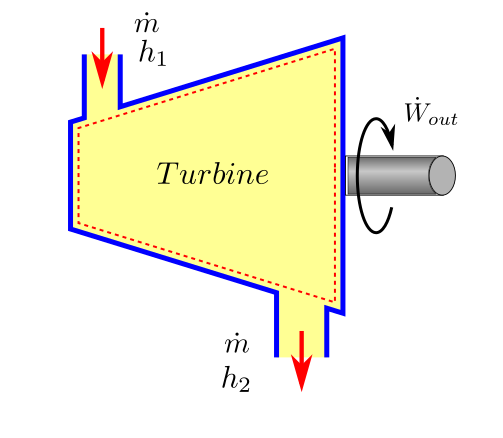

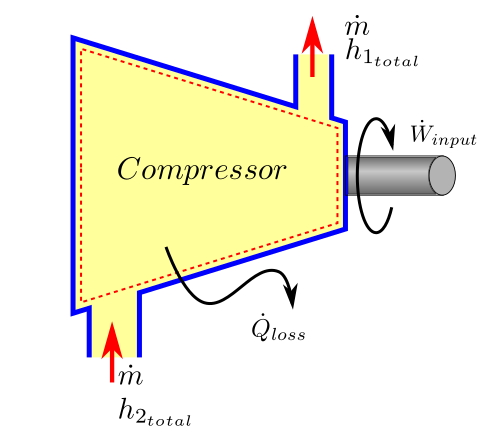

Compressors and Turbines¶

In a compressor mechanical work is spent to raise the pressure of a fluid (compressible fluid), while in a turbine work is obtained by letting down the pressure of the fluid stream. For approximate calculations these devices can be treated as adiabatic i.e. \(\dot{Q}=0\). Further the changes in kinetic and potential energy can also be neglected \(\varDelta{pe}=0\) and \(\varDelta{ke}=0\).

For turbines, a net work is obtained from the device and we can call this work as \(W_{output}\). The first law equation (38) can be written for an approximate analysis case as:

rearranging we get the first law equation as applicable to turbines.

Important

First Law applied to turbines

For compressors net positive work is done on the machine and we can call this work as \(W_{input}\). In a more rigorous performance evaluation such as those adopted by the ASME PTC 10 code for compressor a more accurate approach is adopted. Heat losses from the equipment (\(Q_{loss}\) is not ignored. The affect of change in potential energy is always neglected by codes as well because it is really very small compared to the other energy terms. Kinetic energy term does not directly enter the heat balance equation, but it is still accounted for by making use of the concept of total enthalpy (or stagnation enthalpy). Total enthalpy is defined as:

The first law equation (38) can be written as:

rearranging we get the first law equation as applicable to compressors.

Important

First Law applied to compressors

The heat loss is primarily the bearing loss (mechanical loss) and can be determined by measurement of oil flow rates to bearings and the oil temperature rise, using a known value for the oil specific heat. Surface losses can be measuring the compressor body area, surface temperatures and air temperatures and use convective heat loss rules.

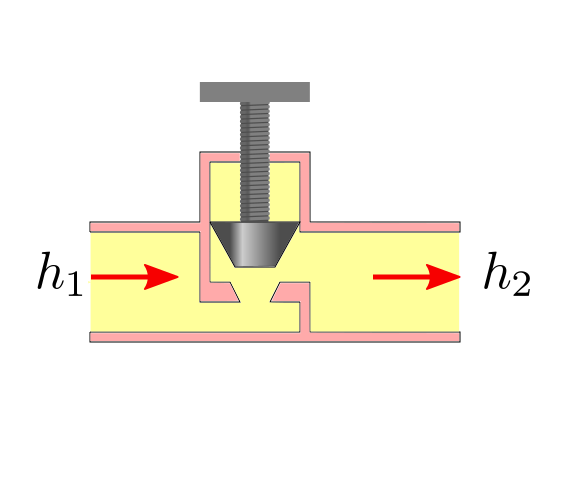

Throttling Valves¶

Throttling valves are flow restricting devices that cause a significant drop in pressure in the fluid. These devices could be adjustable valves, porous plugs or capillary tubes.

No work interaction happens in the device and the heat loss is also considered negligible due to the short interaction time. Thus both heat rate (\(\dot{Q}\)) and work rate (\(\dot{W}\)) are zero and therefore after substituting in (38) we have:

which upon rearrangement leads to the following equation of first law as applicable to throttle valves:

Important

First Law applied to Throttle valves

while, \(h\) remains constant its constituents \(u\) and \(Pv\) could change such that their sum is a constant.

Note

For ideal gases enthalpy \(h\) is a function of temperature \(T\) only. Thus when an ideal gas undergoes throttling the temperature remains same.

However for most real gases, a temperature drop is observed therby implying that there is a fall in internal energy \(u\). This is most notable for refrigerants. For hydrogen, a temperature rise is observed during throttling.

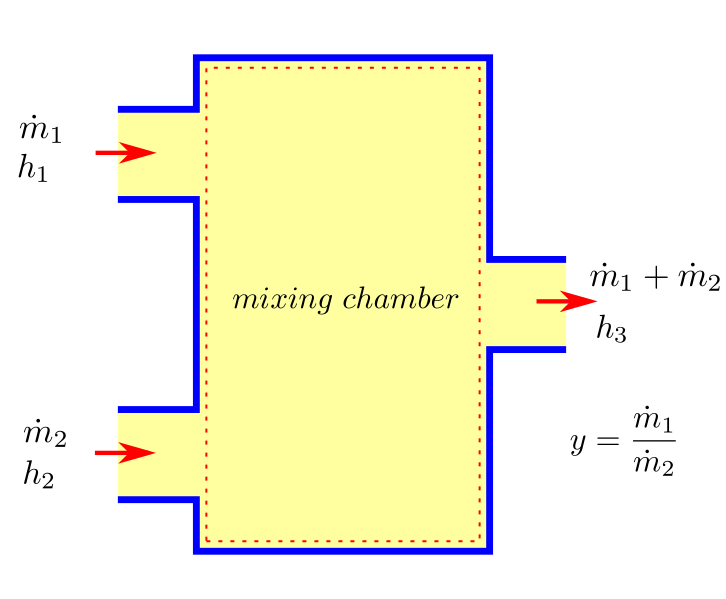

Mixing Chambers¶

Mixing of two streams is a very common engineering problem. For an adiabatic mixing case (which is usually the case), both Heat rate (\(\dot{Q}\)) and work rate (\(\dot{W}\)) are zero. Kinetic and potential energy changes can also be neglected. Therefore after substituting in (37) and some rearrangement we have:

if \(y = \dot{m}_1/\dot{m}_2\), we get upon dividing the above equation by \(\dot{m_2}\) :

upon rearrangment, leads to the first law as applicable to mixing:

Important

First Law applied to Mixing

with rearrangement, if the enthalpy of the stream after mixing is known, then mixing ratio can be expressed as:

where \(y = \dot{m}_1/\dot{m}_2\), is the mixing ratio

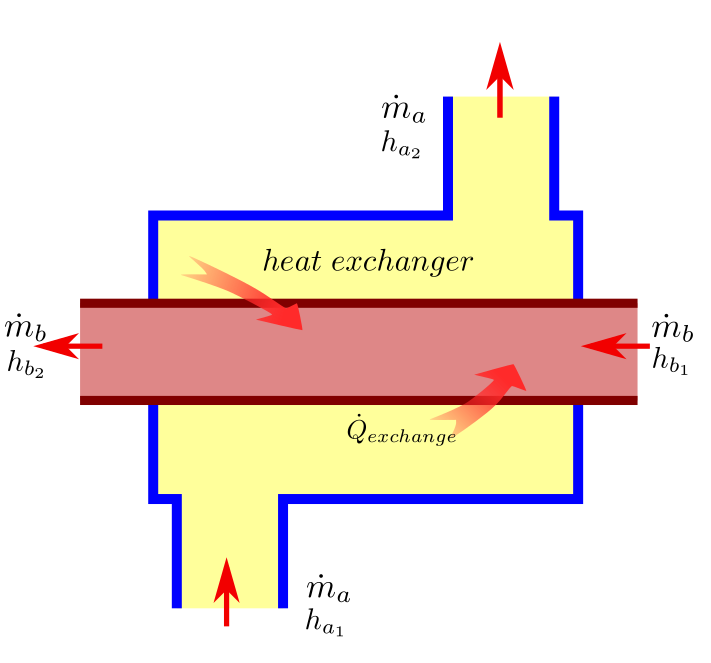

Heat Exchanger¶

Heat exchanger is a device where two moving streams exchange heat without mixing with each other. There is no work interaction in a heat exchanger and assuming adiabatic process (which is a good approximation of heat exchanger), the heat interaction can also be neglected.

Let the two streams be ‘\(a\) and ‘\(b\) and their mass flow rates \(m_a\) and \(m_b\) respectively. Let subscript \(1\) denote inlet and subscript \(2\) outlet as usual. Substituting in (37) we get the first law equation for heat exchanger:

Important

First Law applied to Heat Exchanger